Exploring Avian Soundscapes in Ancient and Restored Woodlands

Figure 1. The ancient woodland (left) and the restored woodland (right).

The focus of my project

Monitoring biodiversity trends is essential amidst ongoing declines, as well as to assess habitat restoration progress. New technologies are providing alternative methods for ecological monitoring, including the use of audio recorders. These recorders offer a promising solution due to their cost-effectiveness and non-invasiveness. All sounds, ranging from birdsong to the whistling of winds, collectively form an environment’s soundscape – its auditory landscape. Researchers are exploring the potential of ecoacoustics, a field examining the soundscape of environments, in ecological monitoring. Birds are particularly suitable for ecoacoustic surveys due to their vocal nature, and they also serve as valuable bioindicators, providing insights into ecosystem health.

My research objectives were to:

- Evaluate variations in bird species richness, diversity and community composition between the ancient and restored woodland.

- Assess differences in bird species detection between human observers and acoustic recorders.

- Investigate how well acoustic indices predict bird diversity patterns.

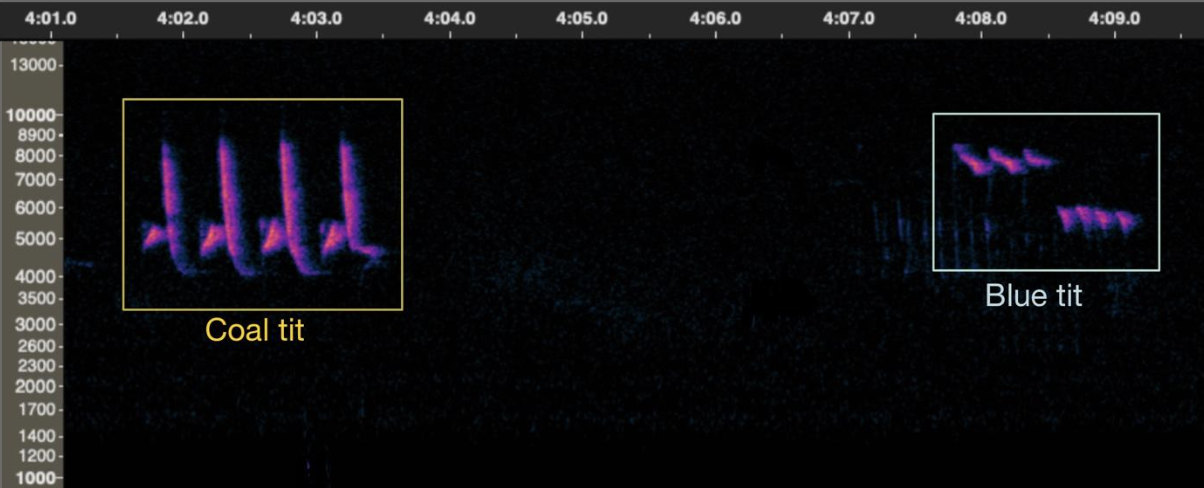

Data collection and processing

Each day, my coursemate Arianna, who kindly assisted me with my fieldwork, and I ventured out at sunrise, the peak time for bird activity. We conducted point counts along designated transects in the ancient and restored woodland, recording all birds heard and seen within a specified radius and time frame before moving to the next point. Additionally, I deployed AudioMoth recording devices (Fig. 2) to capture the woodland soundscapes throughout the morning. Despite their compact size, AudioMoths have impressive recording capabilities, and can capture audio for days, even weeks, on a single charge.

Initial findings and planned analysis

The Eurasian chaffinch was the most common species in both woodlands, followed by the Eurasian blue tit in the ancient woodland and the European robin in the restored woodland. While a similar number of bird species occurred in both woodlands, the specific species differed. During my surveys, treecreepers, long-tailed tits and great spotted woodpeckers were only found in the ancient woodland, whereas bullfinches and dunnocks were exclusive to the restored woodland. I will now conduct statistical tests to determine if there are differences in the number of bird species, their diversity and the bird community composition between the ancient and restored woodland. Even though the species richness was similar, I expect the bird diversity and community composition might vary between the two habitats.

Figure 4. Some of the bird species found during my surveys. Despite the chaffinch being the most commonly recorded species, I didn’t manage to capture a single photo of one. From left to right: Great tit, dunnock, Eurasian treecreeper.

Exploring the surroundings

When I wasn’t conducting fieldwork or analysing audio files, I took the opportunity to explore the estate, as there was so much to see! The trees were covered in beautiful mosses and lichens, lots of plants were awakening after the winter, and buzzards, golden eagles and white-tailed eagles soared overhead. I was also fortunate to spot a couple of porpoises, and observed an otter hunting for its lunch in the loch (Fig. 5).