Beautiful charismatic woods that are filled with bird songs and gentle whispers of wind…

I have had the pleasure of exploring the Kilchoan Estate’s woodlands, hills, and shores for the past three weeks. My main objective was to collect data for my dissertation in Ecological and Environmental Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. My dissertation revolves around the question to what extent rewilded forests resemble those of natural origins.

But I have obtained much more than data. I walked (and sometimes stumbled and fell) through beautiful charismatic woods that are filled with bird songs and gentle whispers of wind through leaves and fern, and whose trees are covered in their own carpet of moss and lichen. If it hadn’t been for my data collection, I don’t think I would have dared to enter forests where I couldn’t see the ground and bracken fern grows taller than me. I learned that sometimes moss does not mean ground but is just air, that I had better listen for streams than look for them because they are hidden underneath the grass, that branches can break off if I just look at them the wrong way and are not to be trusted as aids, and that bracken is most comfortably crossed by finding a way around it.

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 1. One of my favourite views in the Magazine Wood. The fern was a mixture of bracken and a less dominant species and I was happy to see them growing together.

THE PROJECT

My dissertation project is looking at the functional diversity of the herbaceous ground layer in three different woodlands: the Temperate Atlantic Rainforest, the mixed deciduous and coniferous plantation forest, and the oak-dominated woodland around the Interpretation Hub.

Functional diversity looks at the range and value of specific plant traits within an ecosystem. Such traits include adult plant height, stem specific density, leaf area, leaf mass per area, leaf nitrogen content, and diaspore mass. These six specific traits have been reported as critical in determining a plant’s form and function. Within a community of plants, it is expected that these trait values vary between species, mainly because of different growth strategies. In a wider context, plant functional traits relate to how an ecosystem functions and how it responds to external signals, such as drought or air pollution. This can be relevent for deciding how to rewild a landscape to achieve certain services from that ecosystem.

Because the woodlands in question are of different tree compositions, management history, and origin, I am investigating whether and how exactly the herbaceous ground layer is also different and what the driving factors might be. Driving factors for functional diversity can include the tree species composition, the grazing impact and other management practices, climate, or other abiotic factors.

Data Selection

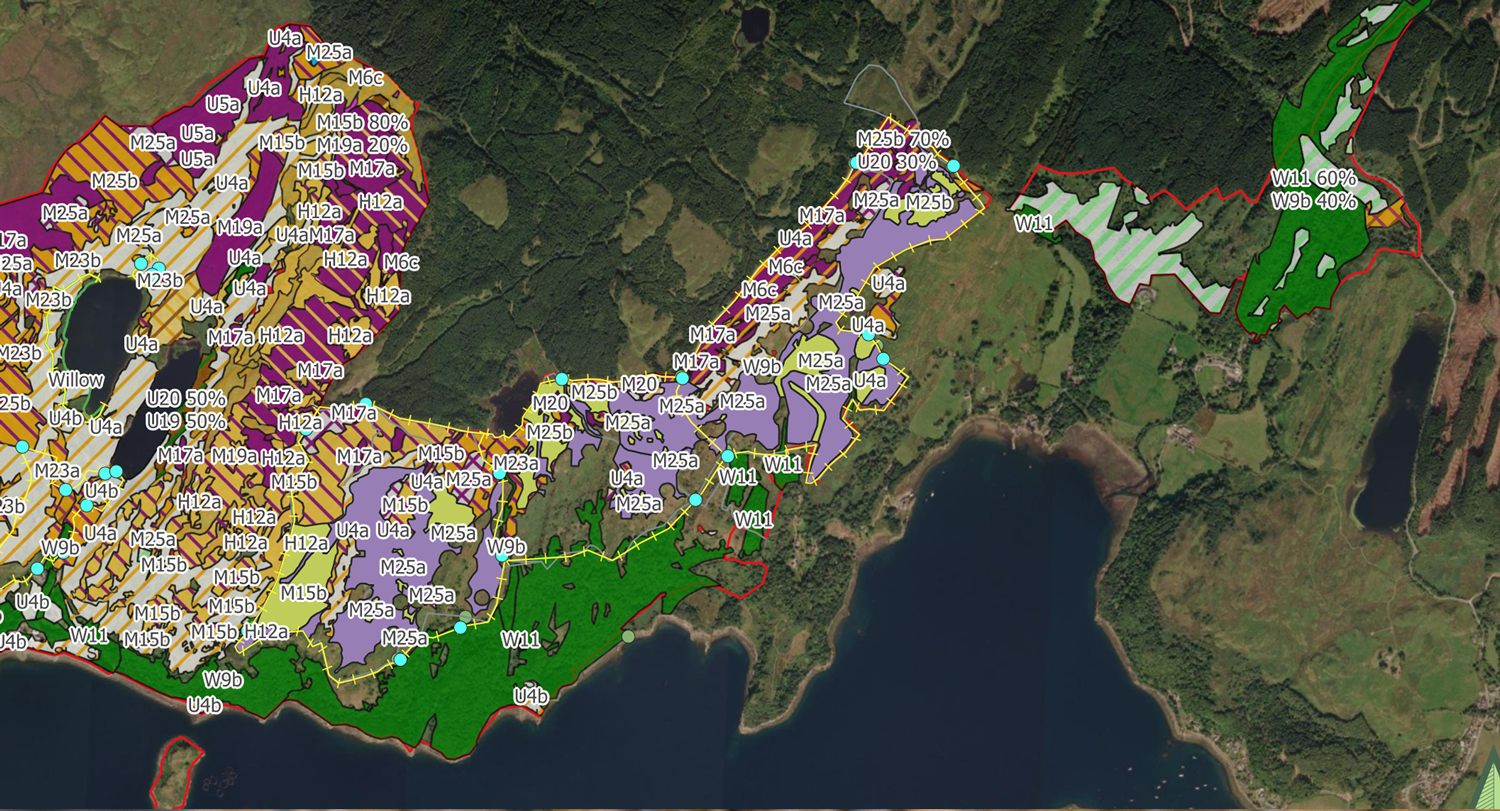

This so-called National Vegetation Classification (NVC) map shows areas grouped by common species, and I used it as a basis for my site selection and data collection (Figure 2). I drew the boundaries of the woodlands that I’m investigating in a software called QGIS. Then I filtered out the areas that were too steep for me to access. And finally, the software generated random locations for me (Figure 3). In the field, I followed the GPS to those random locations (often wandering around in a circle until the GPS caught up with my position). When I found my plot location, I placed my gridded quadrat on the ground and started recording the species as well as their abundance by counting how many grids the species occurred in (Figure 4).

In the event of an unknown plant, I collected a plant sample and attached a note about which plot it came from and its abundance. I would then use several plant guides, both for inflorescence and vegetative parts, as well as the internet and in some instances the help of my supervisors, to identify the plant.

Plot records were completed, synchronised, and backed up every day to ensure that no data would be lost.

Figure 2. The NVC map for Kilchoan. Each code represents a different community of plant species, characteristic for that eco system

Planned Analysis

To prepare the data, I will collate the values of various plant traits for each plant species. This means that I will have a datasheet with each plant I have collected, its abundance, and its value for a specific plant functional trait, e.g., adult plant height or leaf mass per area.

In the first instance, I will analyse the variation of plant trait values between the plots within a particular woodland: How does the plant community in the Temperate Atlantic Rainforest vary? For this perspective, I will calculate metrices such as ‘Richness’, ‘Divergence’, and ‘Dispersion’.

As a next step, I will compare the functional trait values between the plant communities of the different woodlands. How do the plant communities differ between woodlands of different origin and management histories?

I expect that in older forests that have undergone less disturbance, the herbaceous (non-woody) plant community has become more complex and the functional trait space that the values occupy is larger. But the crucial question is how similar the functional diversity of a managed plantation-origin forest is to one of semi-natural origin, and I am very curious to find that out.

Flowers, otters, and seals

When I returned from the forest around 5pm, it felt strange and pointless being inside. And so, after finishing the plant identification from that day, I would take my dinner and my camera and venture to the shore, the arboretum, or the gardens. That is when I saw a common seal sticking its head out of the waves like a bowling pin. And that is also how I saw my first otter, hunting for fish and crabs. It even came to the shore and let me sneak up to take a picture. In the gardens I discovered a bumblebee curled up in a flower, presumably curing a nectar-induced hangover.

I have greatly enjoyed spending most of my time outside, among trees, ferns, hills, and animals. For my first (somewhat) independent field work experience, I have gotten beyond lucky, and I will appreciate this opportunity for a very long time to come. The experience of conducting my own data collection and with the help of so many generous and competent people who know the land so well has been an ideal introduction to field work for me. I can now apply and extend the knowledge and skills I have gained in a much wider context, as well as appreciate other training and scientific papers that were previously less accessible.

I would like to thank the Kilchoan estate, its staff, and its owner for making this possible for myself, as well as for previous and future researchers. It is very generous to share this impressive landscape and the accommodation, and the experience will leave a lasting impression on any visitor.

I wish you all the best and hope to return soon,

Luisa